The concept of lame servers stems from RFC8499 and relates to a situation where something is not right with delegation.

What is delegation?

Delegation is the act of giving away, or offloading, some portion of work elsewhere. In DNS, the specific meaning is to direct a querier to a different server, or servers, for all queries relating to a subset of the namespace that you own.

What is the DNS namespace?

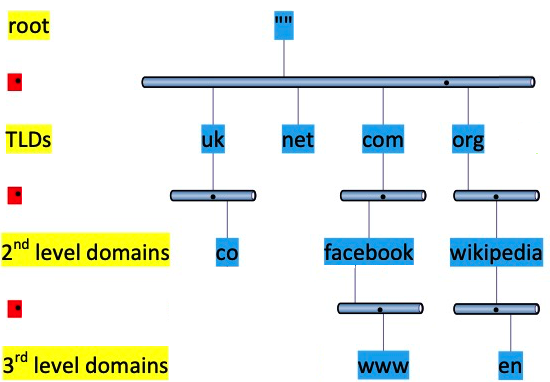

The DNS namespace is an hierarchical organisation of domains, usually represented as an inverted tree: similar to the directory or folder structure of filing systems, where nodes lower down the tree (further away from the root) are children of the nodes immediately above.

The people who run the authoritative DNS servers for the org domain delegate responsibility for (say) the wikipedia domain to them. This is done by inserting into the parent domain (org) DNS records of type NS, which point to the nameservers that are authoritative for the child domain (wikipedia). The people who run the wikipedia nameservers must also list the same NS records and it is at this point that problems can occur.

The way a recursive server finds answers for a domain is to start at the root and work down. It already knows how to find the root servers as these have well known IP addresses that change very rarely, which are compiled into the code.

The recursive server makes a query to a parent (e.g. the root) to learn information about a child (e.g. org). The parent responds with the NS records it has stored for the child: this is known as a referral.

The recursive server then makes another query to one of the child nameservers listed in the NS records returned by the parent.

There are three expectations in this exchange:

-

Any referral must give the recursive server better information than it had before - i.e. improve its view of the world - otherwise the recursive server cannot move forward.

What does 'improve' mean? The recursive server is making iterative queries, starting at the root and traversing the tree downwards, in an attempt to find answers for its clients. At each step it needs to learn information telling it where to try next. If such information cannot be provided by a nameserver then the recursive server can go no further, recursion stalls and it must return SERVFAIL to its client. A nameserver that cannot provide any "where next" information would be classed as lame. -

The child nameserver (as reported by the parent) must respond. A server may not respond for many reasons, such as network issues between it and the querier or a temporary security problem. These on their own do not make a server lame. But if a given server is not intended to be reachable from the Internet - e.g. for company policy reasons - or is not listening on port 53 then that would be lame and it should not be listed as a nameserver in an NS record in the parent zone.

-

If a nameserver does respond - i.e. is a working, reachable DNS server - it must provide information about the domain being queried. It may be a DNS server and it may be reachable, but it may simply not know about the domain being requested. This might arise, for example, when a new delegation has been made from the parent zone but the child NS has not yet been configured with that new zone. This would also be classed as lame.

These situations can arise because the design of the DNS requires that the same information (NS records) be listed in two sets of places - the parent nameservers and the child nameservers - and typically these two sets of servers are run by different people, indeed frequently by different organisations. Human error can therefore lead to mistakes.

Cacheing of incorrect NS records by a recursive server can lead to anything from resolution timeouts at best to obtaining incorrect answers from bogus nameservers at worst.

BIND has always cached lame nameservers separately from valid nameservers and used this information to avoid making any more queries to the lame ones for a period of time - the so-called lame TTL. Specifically, BIND only flags a nameserver as lame if its responses are non-improving (type 1, from the list above).

Type 1 nameservers are cached as lame by BIND because they respond as if they should be able to provide useful information, but don't.

Type 2 nameservers are not cached as lame by BIND because it can't assume anything about a nameserver if it doesn't respond. After a timeout period BIND will retry, using a different nameserver.

Type 3 nameservers are also not cached as lame by BIND because nameserver responses to queries for unknown zones will be errors of some kind, e.g. REFUSED, which again allows BIND to choose a different nameserver and try again.

The BIND lame cache period was fixed at 600 seconds initially. But the lame-ttl option was introduced in version 9.1, allowing operators to tune their servers to better match the particular operating environment. The lame-ttl default value was chosen to be 600s, meaning that behaviour of the lame cacheing feature was unchanged, compared with versions of BIND prior to 9.1.

Following the discovery of the vulnerability now known as CVE-2021-25219 the lame cache has effectively been disabled. The lame-ttl option still exists, but the default value has been changed to zero and any user-set values are silently ignored.